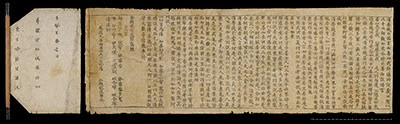

A simple colophon serves to set the stage for both place and origin. While so many discoveries from the ancient past remain dark and unknowable–their humble beginnings shrouded in mystery or intense speculation–the World’s earliest printed book is something far less common for its time: conveniently dated, equivalent to 868 CE.

868 CE Diamond Sutra. End piece with colophon.

It’s colophon reads thus:

“Reverently (caused to be) made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of (his) two parents on the fifteenth day of the fourth month of the Xiantong reign.” — a date equivalent to 868 CE

This copy of the Diamond Sutra was among those works taken from the manuscript cache discovered at Cave 17, the “Caves of the Thousand Buddhas” / Mogao Grottoes cave complex near Dunhuang, in Gansu province, China. Representing an archeological and cultural site of unparalleled significance, given both the vast quantity and breadth of manuscript materials and other artefacts discovered there, the Mogao Caves, or “Caves of a Thousand Buddhas,” were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. This site’s discussion of the 868 CE Diamond Sutra shall continue following a brief orientation to the site itself and some of the key personages involved in its history.

For a compelling video overview of the Mogao Caves site (historical and cultural significance), click below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LbyuIi9BYI

For a UNESCO/NHK video on the site, click below: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440/video

Dunhuang

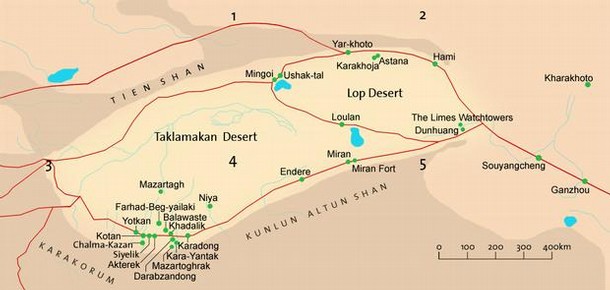

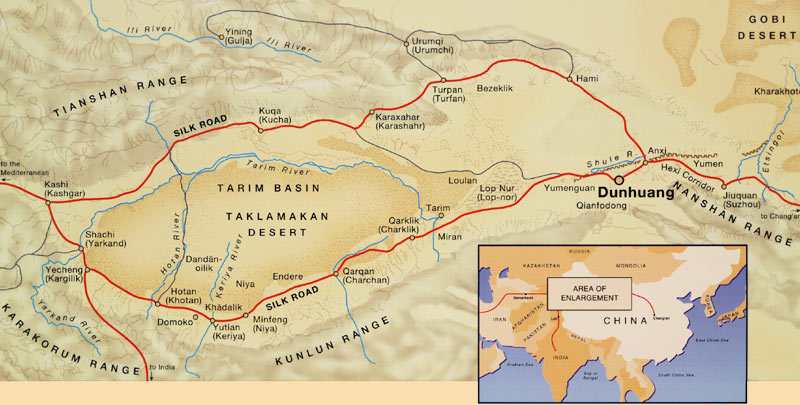

Located at a point where the Northern and Southern land routes of the ancient Silk Road meet, east of the Taklamakan and Lop Deserts, Dunhuang in many ways represented the far Western edge of Imperial Chinese power–a point further underscored by Dunhuang’s relative proximity to a series of early watchtowers (themselves constituting the furthest Westward expansion of the The Great Wall).

Dunhuang’s remote location and dry, arid conditions would prove excellent aids in preserving paper manuscripts and other historical treasures.

Dunhuang and its environs.

Sir Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943)

Sir Aurel Stein was born in Budapest and completed his initial studies in Sanskrit, Old Persian, Indology and philology at the universities of Vienna, Leipzig and Tübingen–with further studies in classical and oriental archeology and languages at Oxford College and the British Museum. Stein also worked briefly as a field surveyor and map-maker while completing a year of conscript service with the Hungarian military. While holding several academic positions within India early on in his career (such as the Registrar at Punjab University in 1887, and the Principal of Oriental College, Lahore from 1888 to 1899) Stein’s passion, it may be argued, was that of the exploration.

Stein became a British national in 1904 and he was later knighted for his contribution to Central Asian studies. Stein’s Silk Road expeditions, like those of his contemporaries, were themselves funded by those institutions to whom he had promised to collect both archaeological and textual artefacts–with the intention that such finds would be allocated proportional to the level of initial funding. For example, Stein’s second expedition (1906-08) was funded 60% by the Government of India and 40% by the British Museum, and any artefacts recovered were to have been divided accordingly. However, records tell us that this was not the case–with the lion’s share of Stein’s ‘recovered’ artefacts making their way directly to London.

Stein is particularly famous for ‘discovering’ the Library Cave / Cave 17 at the Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang. However, it should be noted that Stein carried out three expeditions to the western regions of China between (1900-1916), where he conducted not only archaeological excavations, but geographical and ethnographical surveys, recording much of what he encountered via the technology of photography.

Based on his diaries, Stein published Sand-buried Ruins of Khotan (1903) and Ruins of the Desert Cathay (1912), as well as several more scholarly works. Stein was known for his meticulous attention to detail, his desire to avoid damage and enable preservation of both sites and objects, and the near exhaustive number of detailed photographs, plates and maps associated with his published works.

Ironically, Stein would later be vilified in some circles for his role and methods used in acquiring those manuscripts and treasures taken from the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang.

The Mogao Cave Complex

The creation of the very first cave temple at the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas / Mogao Caves complex is attributed to a Buddhist monk, Lezun. It is said that Lezun, passing by Sanwei Mountain in 366 CE, had a vision of what has variously been termed either “a thousand Buddhas within a cloud of glory” or “shining golden lights, which were like the presentation of ten thousand Buddhas”. Lezun was then successful in having a pilgrim fund the excavation and painting of one of the smaller caves at Dunhuang. Such a humble beginning was oft to be repeated, as shrines and temple decorations were established by those perhaps thankful for having crossed the treacherous Taklamakan Desert or by those seeking merit before making a dangerous journey westward.

As a central point bridging China and the meeting of the Northern and Southern land routes for the ancient Silk Road, Dunhuang was in an ideal position to benefit from the wealth of the passing merchant trade. It was also distant enough from the Chinese capital to escape the short-lived persecution of Buddhist monasteries and other foreign traditions that occurred over a twenty month period during the later T’ang Dynasty (845-846 CE).

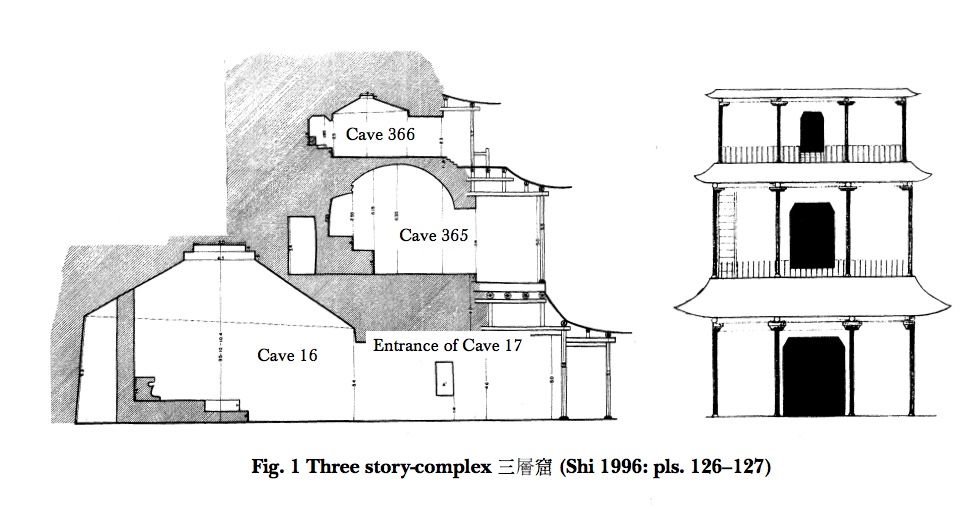

Cave 17

The Library Room / Cave 17 was constructed between 851 CE and 862 CE, in honour of Hong Bian, an important monk in that region, and is an offshoot of the larger Cave 16. Scholars continue to debate the reason as to why the amassed bulk of manuscripts and other artefacts might have first been moved into the small space offered by Cave 17 and ten why this cave might have been sealed. I, personally, like to think of Cave 17 as having played the role of a massive terma, or hidden treasure text. Regardless of reason, the Dunhuang manuscripts were sealed up around 1000 CE, to discovered approximately 900 years later, in 1900 CE.

Map of the three-story cave complex, including Caves 16 & 17, showing front and cut-away view.

Wang Yuanlu, ‘Gurdian’ of the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas

While Sir Aurel Stein is sometimes credited with the ‘discovery’ of the manuscript cache at Cave 17 and with bringing an impressive collection of manuscripts and Buddhist temple art back to Britain and India, it was actually through Wang Yuanlu, the self-appointed ‘guardian’ of the Buddhist caves at Dunhuang, that Stein was eventually given access to the previously discovered cache. Wang Yuanlu had discovered its existence seven years prior, in 1900 CE, when the opening to Cave 17 was uncovered while attempting a restoration of the larger Cave 16.

When Stein had first arrived at the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, he found the ‘Library Room’ to be under lock and key, with Wang Yuanlu away. His subsequent visit saw the previous locked door blocking Cave 17 blocked off behind a wall of brick. What Stein was to do next, in seeking access to the as yet unseen cache of manuscripts, would prove fruitful but in many ways problematic.

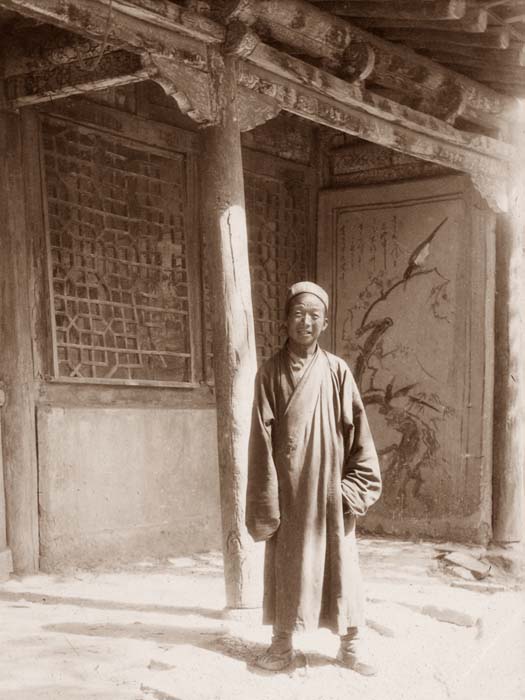

Wang Yuanlu, ‘guardian’ of the Buddhist caves at Dunhuang

“He looked a very curious figure, extremely shy and nervous, with a face bearing an occasional furtive expression of cunning which was far from encouraging. It was clear from the first that he would be a difficult person to handle.” — Sir Aurel Stein

Through the aid of his Chinese assistant, Jiang Xiaowan, Stein was able to convey to Wang his own devotion to the figure of Xuanzang (c. 596-664), a Chinese pilgrim and translator who had brought and translated Buddhist texts from India. Stein intimated his reverence for Xuanzang, akin to that of one’s adopted patron Saint, and that he himself was also pilgrim, having visited numerous holy sites in India. Intimating, of course, that his own aims were the preservation of manuscripts and the Dharma contained therein. For Stein, this tactic would prove to be the key to unlocking the secrets of Cave 17.

“…of my devotion to Xuanzang: how I had followed in his footsteps from India, across inhospitable mountains and deserts; how I had traced the ruined sites of many sanctuaries he had visited and described…” — Sir Aurel Stein

Eventually, Stein was to be given access to an even greater number of those documents contained within the Library Room. Slowly, a process of long negotiation took place via translation, with Stein seeking permission to remove certain artefacts, so as to allow for their detailed study and translation elsewhere. In time Stein would negotiate with Wang Yuanlu to acquire twenty-four cases, heavy with manuscripts, and another five cases filled with carefully packed paintings, embroideries, and art objects. The total cost to the British taxpayer for this treasure trove of artefacts: a paltry £130!

A more detailed survey

During his second Central Asian expedition, Stein was unable to complete a systematic survey of the documents contained within the Library Room / Cave 17 for several reasons. These chiefly being:

- Wang’s general anxiety as ‘guardian’ to the manuscripts created initial difficulties;

- Stein could not read Chinese and was himself not learned in Buddhist literature; and

- The sheer volume of manuscripts and diversity of language scripts encountered.

Stein’s team was, however, able to photograph numerous manuscripts while at the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, allowing many texts to be carried back in photographic form, and later archived as microfiche within the British Museum and The British Library.

The task of painstakingly surveying the remaining manuscripts from Cave 17 would wall to Paul Pelliot, the French rival of Stein. A highly skilled Sinologist, Pelliot’s accomplished knowledge of Chinese allowed him to work at a pace of nearly 1,000 manuscripts per day.

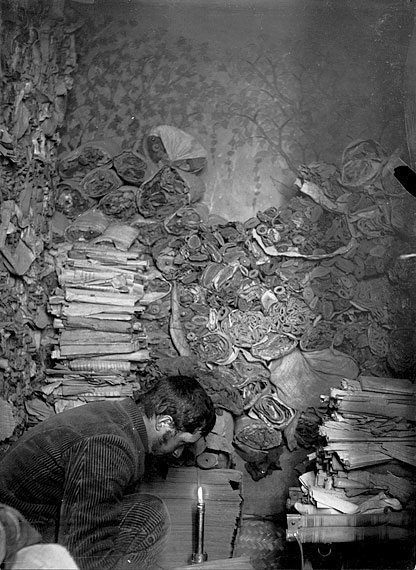

Paul Pelliot in the Library Room / Cave 17, at Mogao Caves. The confined space that Pelliot sits in was made only by Steins earlier removal of manuscripts.

Pelliot’s intellect and rapidity of work led many of his own French colleagues to openly criticize him ad others to claim that he was picking up the drear dregs of what had been left at Dunhuang by Stein. Stein, in his own right, came to Pelliot’s defence, noting that it was only with Pelliot’s own painstakingly detailed survey that the true scope of the find at Dunhuang could be known.

The Diamond Sutra

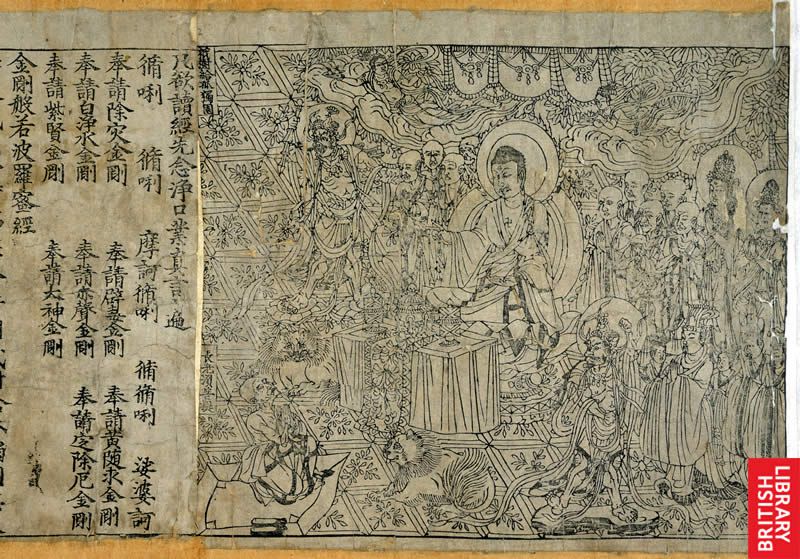

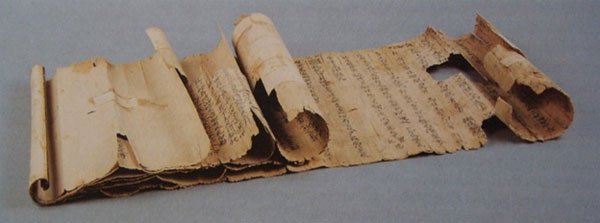

The 868 AD Diamond Sutra text itself is comprised of seven strips of paper, printed using the woodblock method, with a highly detailed illustrated frontispiece–featuring Shakyamui Buddha, assembled arhats, and several Buddhist deities.

Frontispiece to the 868 AD Diamond Sutra.

Over 40,000 manuscript scrolls and other items, such as painted silk temple banners, were to be found in this ‘Library Cave’. The scripts used in such manuscripts included such diverse linguistical offerings Chinese, Khotanese, Sanskrit, Sogdian, Tangut, Tibetan, the Old Uyghur language, Hebrew and Old Turkic.

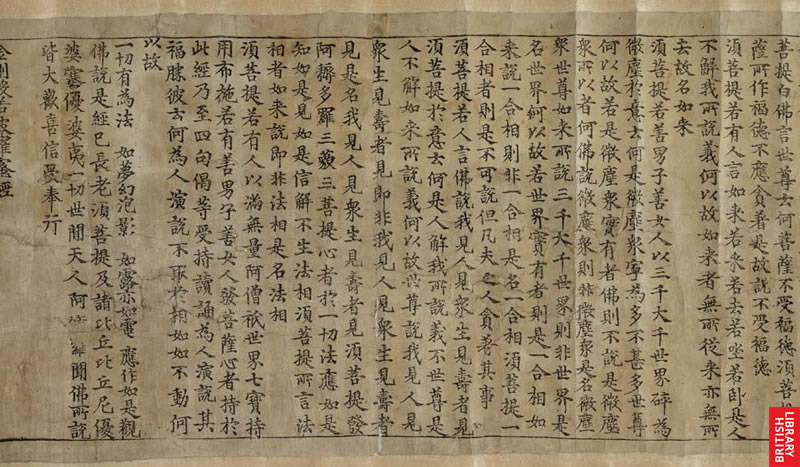

868 AD Diamond Sutra, page 11.

The Diamond Sutra is considered one of the Prajnaparamita or Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, known in Sanskrit as the Vajracchedikaprajnaparamita.

Sutras such as this one were often the focus of pious recitation, sometimes acquiring supernormal qualities such as those normally ascribed to a Buddha or a Bodhisattva. Given its relatively short length, recitation of the Diamond Sutra was extremely popular and believed by some to have such miraculous power as to dispel disaster, disperse poison, or to avert catastrophe.

868 AD Diamond Sutra, frontispiece detail. Subhuti beseeching Shakyamuni Buddha.

Within the printed words of the Diamond Sutra there resides a question, repeated several times by the aged monk Subhuti regarding an aspiring towards the Bodhisattva path:

“How should he control the mind?”

A Bodhisattva is one on the Buddhist path who chooses to forego nirvana and instead seeks to generate both wisdom (prajna) and method (upaya), seeking to perfect oneself and work towards the liberation of all sentient beings. In this way it may be said that the Bodhisattva has one foot in the world and one foot in nirvana. Key to the Bodhisattva path is a true seeing, with the all-penetrating Dharma Eye, into both the relative and the absolute levels of truth. The realization of the essentially interdependent, ’empty’ nature of reality and the impermanence of all phenomena generate a sense of equanimity and, through further attention, the of the generation of compassion (karuna) or loving-kindness. The Bodhisattva idea is seen in both the Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist traditions.

The answers from the Buddha vary but contain within them a common tread of wisdom: a Bodhisattva must not confuse the relative with the absolute, must abide not within ‘self’, and must strive to be charitable towards others. What is described below is a real world engagement of wisdom and compassion via skillful means or method.

“All things things that have characteristics [relative] are false and ephemeral [thereby impermanent]”

“If a Bodhisattva abides in the signs of self, person, sentient being, or life-span, she or he is not a Bodhisattva”

“Practice charity while not abiding in charity”

To listen to an English translation of the Diamond Sutra, click the link below: http://diamond-sutra.com/audio-reading-of-diamond-sutra/

To scroll through the 868 AD Diamond Sutra in its entirety, click below: http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/?id=1c92bc7e-8acc-49b3-9a27-b5ad8f44230a&type=sd_planar

Click below to hear a TBL talk by Susan Whitfield on the Diamond Sutra.

Conservation

As with other historically and culturally significant sites and materials, conservation of the Mogao Caves, as well as the dispersed artefacts taken from this site, have faced several key issues. These include:

- Poor technique on the part of some early archeologists and their crews, whose main effort had been the removal of artefacts for their own museums or institutions (e.g. murals roughly sawed from cave walls; inadequate shipping materials or methods; artefacts left exposed to the elements; etc.);

- Earlier attempts at conservation which proved problematic or deleterious to the manuscripts or objects themselves (as was the case with the 868CE Diamond Sutra);

- Dispersal of artefacts among numerous nations and institutions has resulted a lack of a truly comprehensive and unified and conservation effort (funding, methods, etc.) for items not currently part of the UNESCO site;

- Destruction of items due to war and conflict (e.g. Berlin); and

- The age and previous condition of the materials involved.

Other Treasures

While the manuscript cache at Cave 17 may be best know for it’s 868 CE Diamond Sutra, I would be remiss if I were not to highlight some of the other significant documents and artefacts associated with this site.

The above pictured Chinese-Tibetan Lankavatara Sutra, constructed using a concertina format, is arguably one of the most interesting, and beautiful bilingual manuscripts from Dunhuang. The Chinese text, written in black ink, is a commentary on the Lankavatara Sutra. The Tibetan text, written in red ink between the lines of Chinese, is the Tibetan translation of the sutra.

For more on this Chinese-Tibetan Lankavatara Sutra, click below: http://idpuk.blogspot.mx/2015/11/a-chinese-tibetan-bilingual-buddhist.html

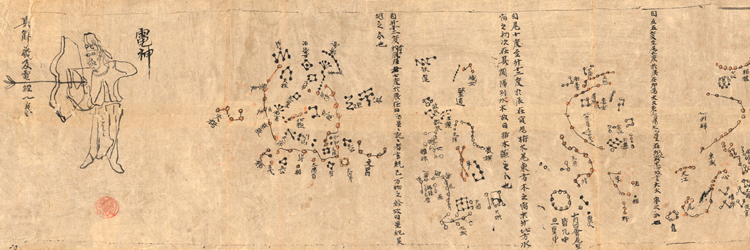

Another important manuscript is an early Chinese star chart containing more than 1300 stars, believed to have been composed during the 7th century CE. It has been offered as “the oldest known star chart from any civilisation and the first pictorial representation of the classical Chinese constellations”.

For more info on this early Chinese star chart, click below: http://irfu.cea.fr/Sap/Phocea/Vie_des_labos/Ast/ast.php?id_ast=2615

The space here is far too brief to adequately detail even a fraction of those brilliant treasures resulting from the rediscovery of the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang and especially of the Library Room now known as Cave 17. While some may bemoan the less than scrupulous means by which some of the artefacts of the past have made their way into our western museums and and available to our institutions of learning, the focus moving forward must be, I would argue, to catalogue and preserve what does remain extant. The efforts of the International Dunhuang Project, the British Library, and the UNESCO site at Dunhuag to preserve, digitize and make accessible those manuscripts and art treasures from Dunhuang have served as critical beginnings towards this effort.

Further links and resources

For the current Wikipedia page describing the Mogao Caves, click below: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogao_Caves

For the International Dunhuang Project (IDP) – Silk Road Online, click below: http://idpuk.blogspot.mx/

To see a Getty Conservation Institute lecture on “Dunhuang as Nexus of the Silk Road during the Middle Ages”, click below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jR3I4ZHRp4

To see a Getty Conservation Institute lecture (Valerie Hansen, Yale University) on the historical context of the Library Cave and Thousand Buddha caves at Mogao, and city of Dunhuang and surrounding region – “The World in the Year 1000: View from Dunhuang”, click below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xFDWkAps8L8